Many early stage enterprise software companies aren’t profitable. Anirban discusses one approach to understanding the underlying profitability of these businesses.

June 25, 2022

If you are a software as a service (SaaS) investor, you are undoubtedly familiar with the land-and-expand model. Land-and-expand refers to the idea that a company might initially sell a customer just one or two products. Over time, as customers start to appreciate the value proposition of the company’s products, they will expand usage to other products in the portfolio. And this idea isn’t limited to the sale of new products. A company could initially sell to a subset of a large enterprise customer, for instance, to one division. Then, over time it could sell more seats for the same product. Or for usage-based products, the expansion might come via more use of the software, which in turn results in more revenue.

Most SaaS companies report their progress on the “land-and-expand” front using the dollar-based net retention rate metric (DBNR). DBNR tells us how much revenue customers generate in a measurement period, assuming this cohort generated 100 units of revenue in the year-ago period. Therefore, if DBNR is 120, it means customers from a year ago, including churn and upsells, are now generating 120 units of revenue. Sometimes, DBNR is measured in terms of annual recurring revenue (ARR) changes, but for our purposes, it is simpler to use sales instead of ARR.

Software investors love DBNR. Higher DBNR values indicate client satisfaction, and increased usage might suggest that software solutions are increasingly ingrained in their customers’ workflows. That’s good because it is suggestive of budding switching costs.

But I like this metric for another reason. DBNR can also provide a glimpse into the underlying profitability of the company.

Let me explain.

For illustration, I will somewhat simplify, but that shouldn’t deter the core message. If we look at the Sales & Marketing (S&M) function of the land-and-expand model, then we can bifurcate it into two components. A portion of S&M is dedicated to “expanding” relationships, while the other part would be about “landing” new customers.

In general, newly landed customers don’t immediately contribute revenue. Once a deal is signed, there will likely be some lag before the software is deployed, which might mean using professional services and training to get the customers going. The point is – there’s usually some lag before new logos start translating into actual dollars.

On the other hand, “expansions” are from the activity of existing clients in the reporting period. It is not about future sales if we are oblivious to the recurring nature of SaaS revenue. Put another way, expansion revenue is currently being recognized, while new logo wins are making their way to the Remaining Performance Obligations (RPO) metric.

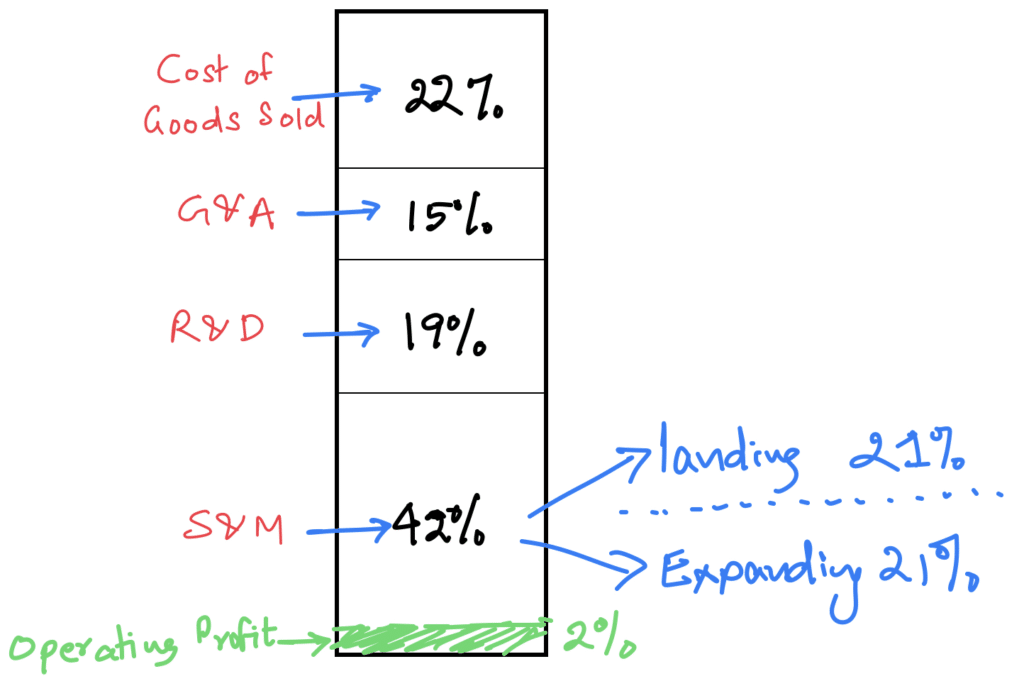

As an example, let’s look at Cloudflare‘s (NYSE: NET) recent earnings report. The company spent 42% of its revenue on Sales & Marketing. The company also reported a DBNR of 127%. Cloudflare doesn’t break up how Sales & Marketing are split between “retention/expansion” versus “landing” of customers. So we are left with some guesswork here, but if we suppose that the split in half, then 21% of the S&M spend would be for future revenue. So, we would have a business where the existing customer base is growing at 27%, with Cloudflare’s operating margin increasing from 2% to 23%. That’s solid underlying profitability.

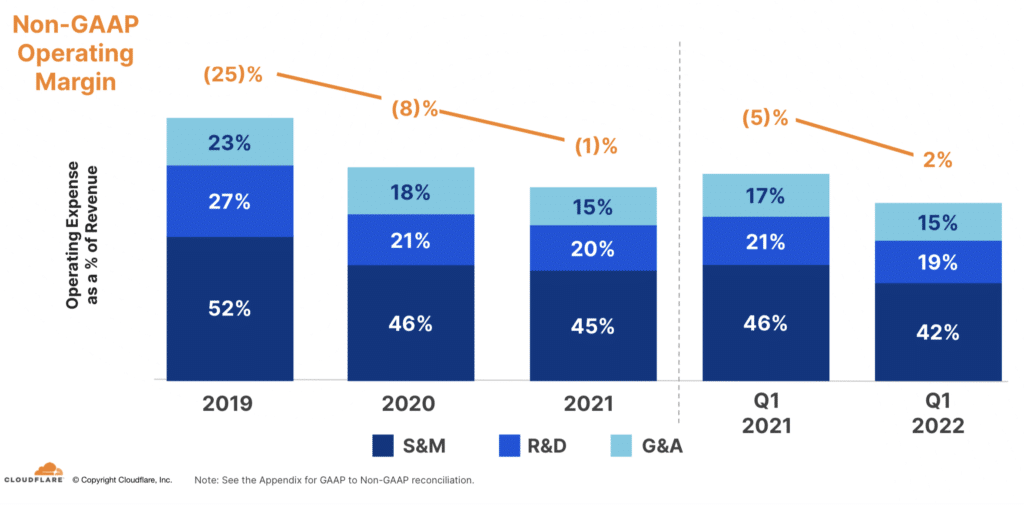

Source: Cloudflare Q1 2022 presentation.

Source: Author illustration.

Of course, this is somewhat of a theoretical exercise. It can be argued that if we stop bringing new customers, then we eventually wouldn’t have any further upsell opportunities after we have exhausted the customer base. That’s true. However, the flipside of the argument is that many next-generation SaaS companies are generating 120% or more DBNR while substantially increasing their revenue base. In other words, the underlying profitability continues to grow as the business gathers steam!

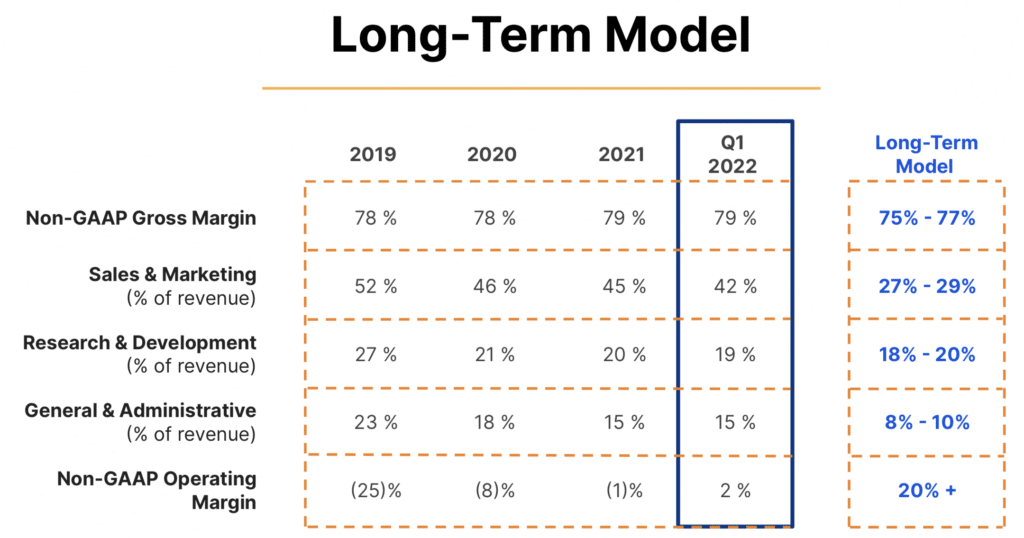

Source: Cloudflare Q1 2022 presentation.

But perhaps the best way to reconcile what I am saying is to compare it with what CFOs of these firms tell us is their longer-term objective. In Cloudflare’s case, if we look at the chart above, their goal is to deliver a 20%+ operating margin at scale. As I have just illustrated, the company can provide that margin right now, if it chooses to, by simply cutting down on future growth. But that would be silly because we would get 20% operating profit on a much smaller base.

Already a 7investing member? Log in here.