In the second quarter, three different RNAi drug candidates or drug products demonstrated the ability to reverse three different diseases.

June 23, 2021

Genetic medicines have the potential to treat the root causes of disease. Rather than inhibiting proteins or mopping up molecular messes, genetic medicines can mitigate the formation of disease-driving proteins altogether or restore protein levels to promote health.

Although there are many therapeutic modalities in the field of genetic medicines, individual investors have been most excited about gene editing tools such as CRISPR-Cas9. The valuations of publicly-traded CRISPR companies suggest investors have very high expectations — perhaps unreasonably high considering the general lack of meaningful data.

In the second quarter of 2021, three different drug candidates or drug products based on RNA interference (RNAi) have demonstrated the ability to reverse three different diseases — all with convenient dosing. Wall Street hasn’t factored these results into market valuations of CRISPR stocks just yet, but investors must consider how new data might affect commercialization outcomes for first-generation CRISPR gene editing.

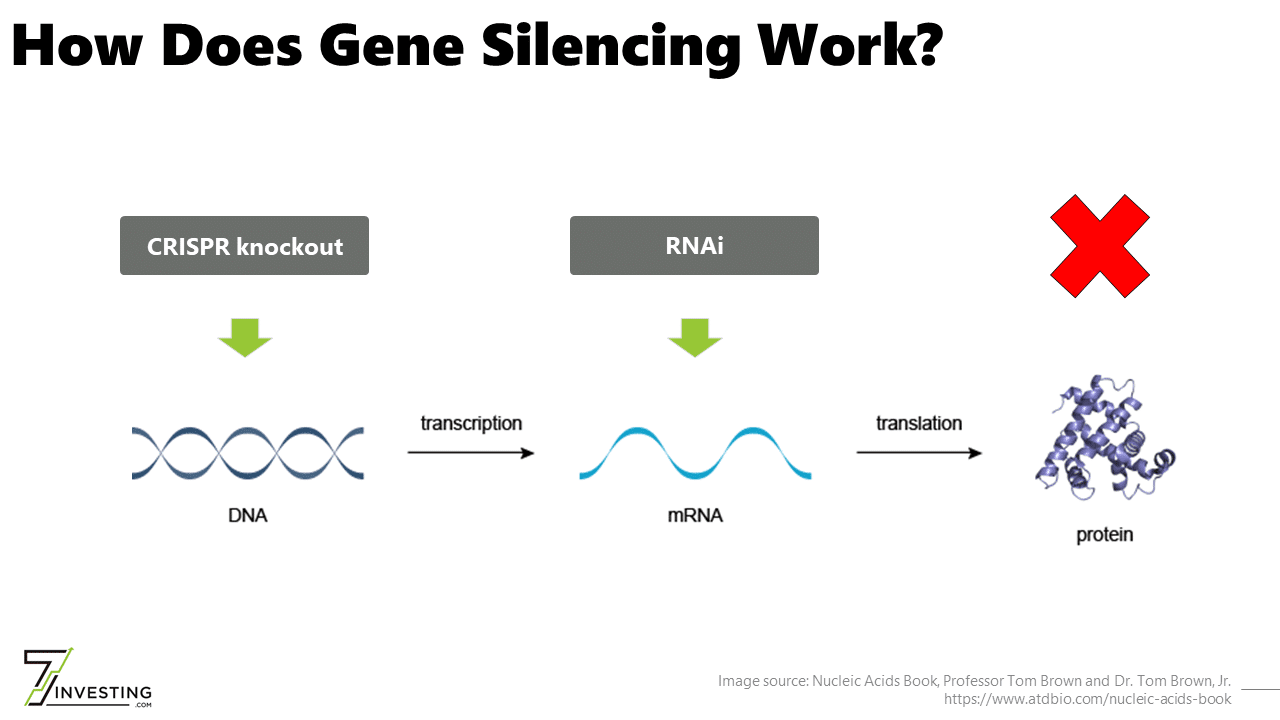

The Central Dogma of Biology states that DNA makes RNA makes proteins. Although RNAi works directly on RNA and not DNA, the approach is still considered gene silencing because it stops a gene from ultimately producing proteins. The therapeutic modality can only reduce protein levels and cannot increase protein levels or correct genes.

That’s not such a bad limitation considering proteins are the drivers of health and disease. Indeed, the presence or accumulation of misfolded proteins is the primary driver of many genetic diseases. Recent data readouts from Alnylam Pharmaceuticals (NASDAQ: ALNY) and Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals (NASDAQ: ARWR) demonstrate the potential of RNAi drug candidates and drug products to not just treat disease, but reverse it:

In April 2021, Alnylam announced that vutrisiran met all primary, all secondary, and most exploratory endpoints in a phase 3 study in hereditary ATTR (hATTR) amyloidosis. The drug candidate reversed polyneuropathy (nerve damage) in the majority of patients, which is one of the hallmarks of the disease. An ongoing study will evaluate the drug candidate’s ability to treat or reverse hATTR cardiomyopathy (enlargement of the heart that causes heart disease).

In April 2021, Arrowhead announced that ARO-AAT led to fibrosis (liver scarring) improvements in four of five evaluable patients with alpha-1 antitrypsin (A1AT) liver disease at 48 weeks. All nine patients in the study achieved improvements in histological globule assessment, a measure of liver function, at 24 weeks.

In May 2021, Alnylam announced that lumasiran (Oxlumo) demonstrated improvements or stability in nephrocalcinosis (kidney stones) in 79% of evaluable patients with primary hyperoxaluria 1 (PH1). The formation of kidney stones is the primary hallmark of the disease and why patients often require kidney and liver transplants. Those numbers may improve with earlier treatment, targeted genetic testing, and/or longer duration of treatment.

All three of these RNAi drug candidates and drug products are administered with convenient subcutaneous dosing (“a simple shot”) once every three months after treatment initiation. That’s an important distinction from patisiran (Onpattro), the first RNAi drug to earn regulatory approval, which is administered with an 80-minute intravenous (“through an IV”) injection every three weeks. Onpattro was the first and last RNAi drug to utilize prior-generation technology. The therapeutic modality can almost certainly achieve less frequent dosing than once every three months.

Alnylam is exploring using a 50 mg dose of vutrisiran once every six months. Meanwhile, the company recently unveiled a preclinical hATTR program utilizing a new chemistry intended to be dosed once per year, with completely reversible effects, and with deep reductions in protein levels (>90%) that could match those promised by gene editing. The company is also working on oral formulations for certain diseases, while others in the field are exploring biannual or annual dosing for gene silencing outside of the liver. These breakthroughs obviously would not match the one-and-done convenience promised by gene editing, but they might be convenient enough for most doctors and patients.

[su_button url=”https://7investing.com/subscribe/?marketing_id=79194″ target=”blank” style=”flat” background=”#84c136″ color=”#000000″ size=”6″ center=”yes” radius=”0″ icon_color=”#000000″]Tired of surface-level analysis? Subscribe to 7investing today for more in-depth biotech insights![/su_button]

Intellia Therapeutics (NASDAQ: NTLA) is initially focused on developing in vivo drug candidates for gene silencing applications. The approach uses CRISPR-Cas9 to “knock out” a gene by disrupting the sequence responsible for its expression. At a high level, the clinical objective of reducing protein levels is identical to that of RNAi.

Not surprisingly, there’s plenty of overlap between the company’s knockout pipeline and those of RNAi drug developers. Intellia Therapeutics’ lead in vivo drug candidate is taking aim at hATTR, while the next most-advanced program is targeting hereditary angioedema (HAE), another Alnylam target. Discovery-stage programs that might use knockouts include PH1, A1AT liver disease, and others that promise to square off with RNAi drug candidates and drug products.

On the one hand, gene knockouts promise to drive deeper reductions in protein levels than current-generation RNAi. They would also represent a permanent, irreversible change to a patient’s genome. Although CRISPR gene editing compounds must be administered intravenously, a single dose is the most convenient dosing.

On the other hand, there are clinical and commercial challenges for investors to consider. First-generation CRISPR gene editing requires making a double-stranded break in the genome, which is repaired with mutagenic (“mutation-causing”) processes. Double-stranded breaks can result in random insertions and deletions of genetic material far from the cut site, while there’s evidence that sections of chromosomes can be rearranged. Each is a hallmark of cancer cells. (It’s important to note that these are on-target effects inherent to CRISPR gene editing, separate from the more familiar off-target effects discussed in the media, which are largely exaggerated.)

The long-tail safety risks from on-target effects might not become evident until years after clinical development is completed. Therefore, drug candidates utilizing CRISPR-mediated knockouts might generate promising safety and efficacy data in clinical trials, but regulators might balk at speedy approvals for knockouts or require long-term patient monitoring. This is especially true considering many indications being targeted by knockouts will likely have safe, effective, and convenient treatments provided by RNAi. In other words, although these indications are called “rare diseases,” regulators probably won’t be under pressure to approve knockout drug candidates for the sake of patients.

Even if knockouts earn regulatory approval, it could be difficult to dislodge RNAi treatments. For example, by the time Intellia’s lead drug candidate reaches the market (assuming it does), most global hATTR patients will be taking treatments from Alnylam. An estimated 3% of global patients are taking the relatively inconvenient Onpattro, although many more could be eligible for treatment with vutrisiran should it earn regulatory approval in 2021 or 2022. That could result in Intellia boasting an approved knockout drug product and frustratingly little opportunity to capture market share. It’s more likely that the market experiences cutthroat pricing competition between RNAi treatments and gene knockouts, which would be great for patients, but perhaps not so great for the drug developers arriving a little too late to the market.

Wall Street isn’t pricing in these potential clinical and commercial challenges for Intellia Therapeutics, which is valued at an astounding $5.2 billion. Instead, analysts seem content penciling in blockbuster potential for drug candidates that have no clinical data (the first batch of data for the hATTR program are expected any day now) and face an increasingly complicated competitive landscape. Although gene knockouts comprise only one of three possible uses of CRISPR gene editing (alongside in vivo gene insertion and ex vivo gene editing for cell therapies), individual investors need to be mindful of valuations that might be driven by non-market factors, such as hype and media exposure.

RNAi remains the genetic medicine with the most immediate commercial potential. The first RNAi drug was approved in 2018. By the end of 2021, that number could increase to five — with potentially dozens more on the way in the next decade. Alnylam Pharmaceuticals estimates that the probability of success that one of its liver-directed drug candidates advances from phase 1 completion to regulatory approval is 60%. For perspective, the overall industry average for any drug candidate in any disease is just 9.6%. It’s not even close.

Of course, RNAi is relatively limited. It can only reduce protein levels and cannot permanently correct mutated mRNA transcripts or genes. Then again, there are diseases in which doctors wouldn’t want to make irreversible changes to a patient’s genome, such as alcohol use disorder (“alcoholism”) or many cancers.

There will undoubtedly be overlap with more versatile tools, such as various gene editing tools or next-generation oligonucleotides. One-and-done treatments using CRISPR-mediated knockouts might result in deeper reductions in circulating protein levels than current-generation RNAi treatments. It’s also possible that other genetic medicines will enjoy a similarly high probability of success as liver-directed RNAi compounds — we just don’t have the data yet.

That said, investors have to remember that successful clinical development is just the beginning. A product that successfully knocks out a disease-causing gene might still struggle to achieve commercial success due to established RNAi treatments that provide a strikingly similar benefit for patients. If RNAi treatments can be dosed once per year with convenient subcutaneous dosing and reverse disease is most patients, then it could be very difficult to dislodge those products. Doctors, patients, and regulators could also balk at the long-tail safety risks posed by the on-target effects of first-generation CRISPR gene editing.

The most important takeaway for investors interested in genetic medicines is simple: Focus on the outcome, not the underlying technology used to achieve it. All genetic medicines add value on a case-by-case basis. Understanding the nuances of the technical opportunities and challenges can help to drive your portfolio’s returns and help you to avoid chasing momentum.

Maxx Chatsko is a Lead Advisor at 7investing, a stock recommendation service that encourages individual investors to adopt a long-term mindset. We transparently report the performance of all past and present recommendations. You can see our cumulative, real-time performance at any time, but only subscribers can see the stock-by-stock breakdown, research reports, continuous company updates, and more.

Already a 7investing member? Log in here.