Free Preview

New AI tools could supercharge the emerging field of generative biology. The therapeutics segment might be a natural fit.

“Synthetic biology and artificial intelligence will emerge as the two most dominant technologies of this century.”

-Jim Collins

One of the technology world’s most cutting-edge fields in recent years has been synthetic biology.

By genetically rewiring the cells of living things, scientists could reprogram them to do entirely new tasks that were useful for industrial applications.

One example has been the synthetic engineering “smart crops.” By using products to enhance their nitrogen uptake, they could grow stronger and with fewer diseases (not to mention reduce waste waste and pollution). Another has been biodegradable plastics. By synthetically-engineering sugarcane or wheat to be even more rich in cellulose, they could hold their structure and still easily break down in landfills. Other examples include bioengineering algae for the use in biofuels or medicines that are derived from living therapeutics.

Artificial intelligence has long been instrumental in progressing the synthetic biology field. Companies like Twist Bioscience (Nasdaq: TWST) pioneered the use of AI tools to design the specific genes that were used to create these innovative new products.

But AI is becoming much more capable these days. It’s creating those genes much more quickly, more iteratively, and much less expensive. And that’s going to introduce an entire new field of “generative biology” for investors to capitalize on.

Programming Life

The foundation of synthetic biology is programming the “circuit functions” of the genes it creates. Just like a math equation uses addition or multiplication signs to derive a final answer, a genetic circuit arranges the biological inputs of a cell in a way they will encode RNA proteins for a cell to perform a very specific function.

This process is iterative. Thus far, it’s often been trial-and-error — where gene circuits have been designed, tested, re-designed, re-tested, and then optimized over months or even years.

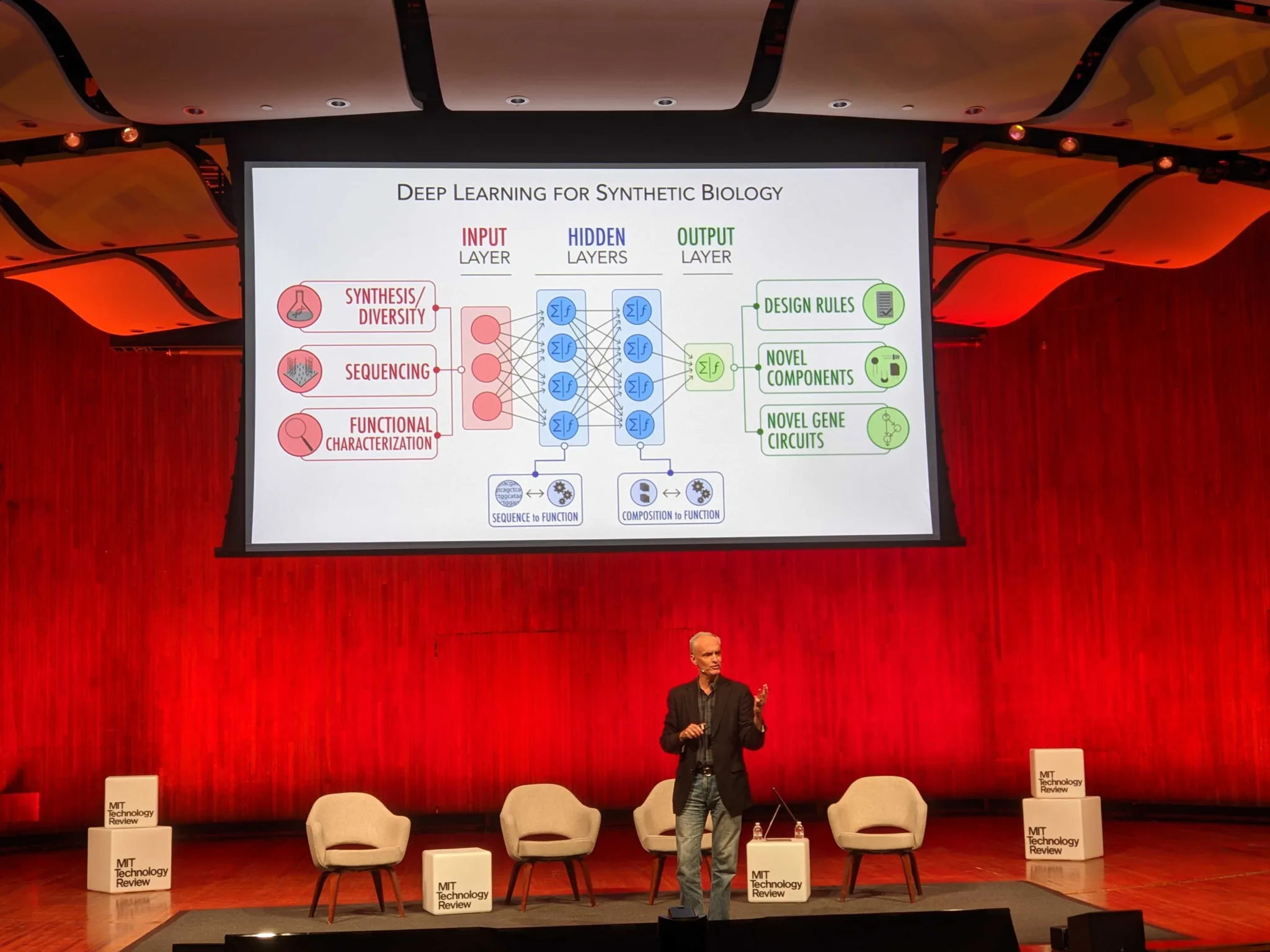

More recently, neural networks have been employed to infer the design of the cell and its ultimate goal. From there, it can suggest the novel components to use for a unique and highly-optimized novel gene circuit.

MIT professor Jim Collins is generally regarded as the inventor of the synthetic biology field. At MIT’s recent EmTech conference, he explained that we still only have about two dozen components that can be used to create those gene circuits. Yet he believes AI — and specifically generative AI — will expand this number of components significantly.

RNA switches can use deep learning to predict 3D structures of proteins, and then produce “RiboFold” RNA components.

Image: Jim Collins, the father of synthetic biology, at MIT’s 2023 EmTech Conference

Will Synthetic Biology Come…Back to Life?

Even as much as I love innovation, I also recognize that neat science doesn’t always result in phenomenal investment returns.

The synbio industry as a whole is no stranger to hype. Years ago, Craig Venter’s Synthetic Genomics was supposed to revolutionize the energy industry by mass-producing algae-based biofuels for Exxon. Yet due to challenges in process controls and prohibitively-expensive economics, the project never got back the R&D scale. Zymergen was worth $3 billion in its 2021 IPO on the promise of “partnering with Nature” to create synthetically-engineered products that would replace those made by petrochemicals. Yet due to a plethora of technical issues, it never brought any of its products to market and ended up getting acquired for pennies on the dollar.

Is this time different? Are AI tools now good enough to make synthetic biology technologically and economically efficient enough to finally be safe to invest in?

The answer lies in scalability. Academic exercises and promising results in the lab should never be confused with commercial production volumes. Investors should be aware of this as well, and exercise a boulder of caution when approaching in synthetic biology.

“We need to start exploring where biology is better than chemistry. Not so much in industrials. But definitely in therapeutics and in diagnostics.”

Yet still, there’s no denying that synbio’s pace of innovation is happening at a breakneck speed. The therapeutics sector is much less price-sensitive than industrial products.

One opportunity could be treating cholera. When we get exposed to dirty water, cholera often appears as a toxin in our gut. Scientists could re-engineer the receptors of our gut, to produce the genetic circuits that would selectively block or control cholera as soon as it were identified. It’s not entirely different than synthetically engineering those smart crops for better nitrogen uptake.

The new-and-improved capabilities of generative AI might be best applied to the highly-demanding and-yet highly-rewarding therapeutics sector. This appears to be a the right product-market fit for the future of generative biology.